If you try to find the history of Tracy, California, before 1878, you can stop looking. You won’t find it.

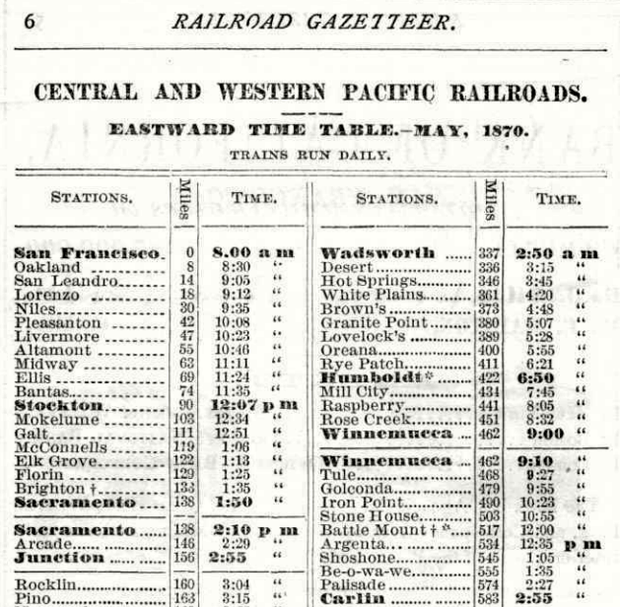

Before 1878, the district located at the southern edge of San Joaquin County on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley was a collection of small towns and villages in an area known as Tulare Township. (Tulare Township should not be confused with Tulare County or the city of Tulare, which are located about 160 miles southwest of Tracy in Central California.)

The villages that sprouted up here in the 19th Century included Bantas (later known singularly as Banta), Ellis, Midway and Lathrop, settlements that began as trading posts, stagecoach stops or, in the case of Midway and Lathrop, were created because the transcontinental railroad was built there.

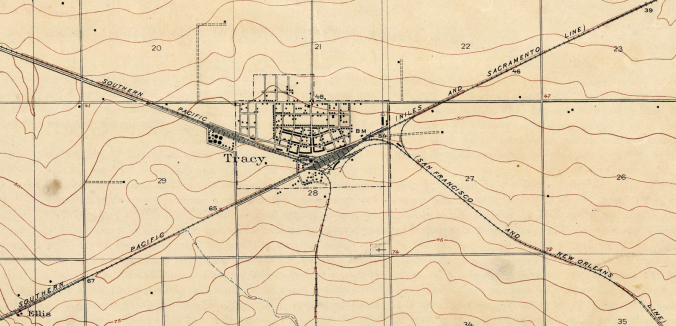

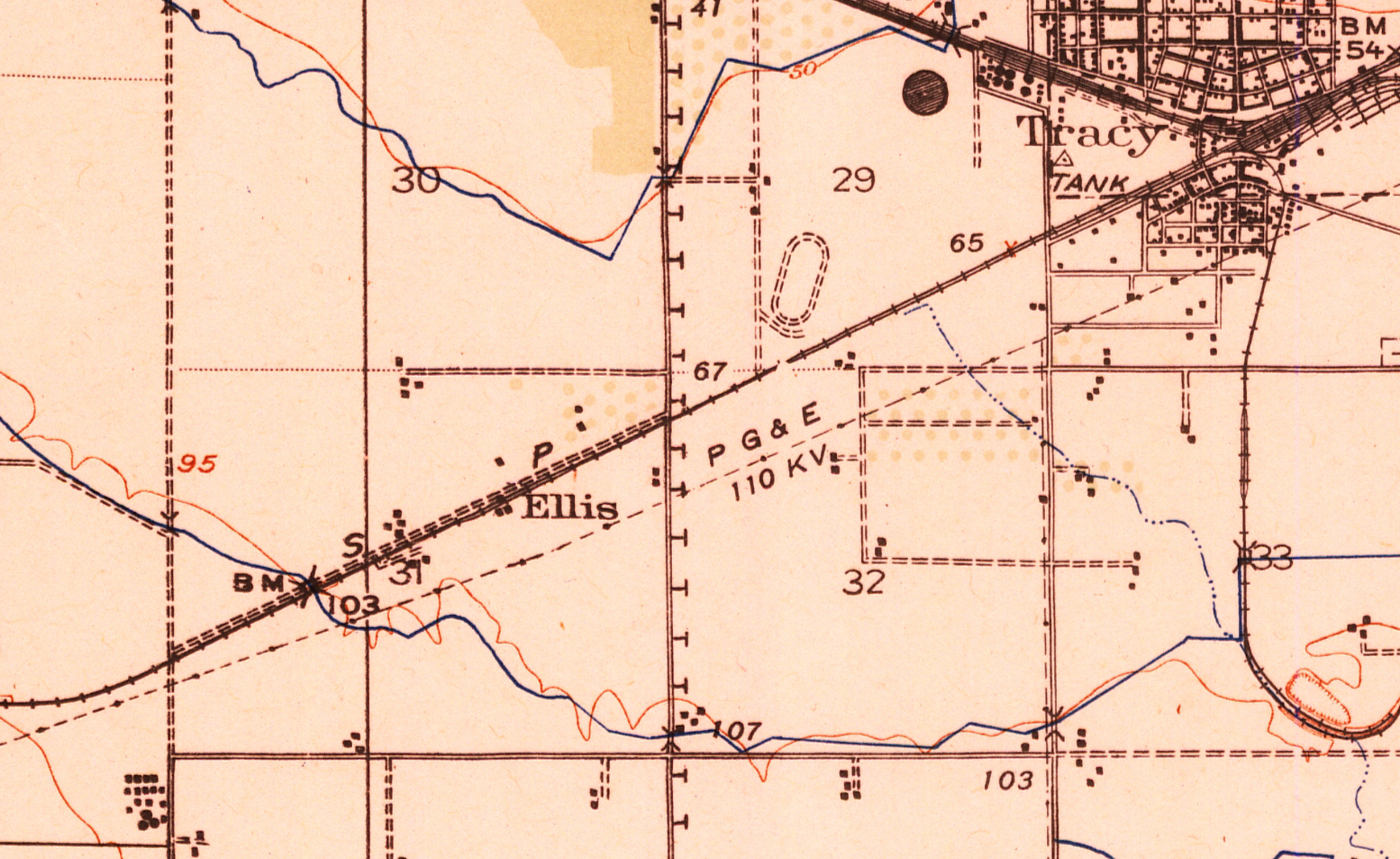

In fact, looking at this map (below) from 1877, Tracy does not even appear yet. One year before it was founded, the space between the villages of Ellis and Bantas, connected by the original Western Pacific Railroad, is uninterrupted by any trace of Tracy:

Tulare Township in an 1877 map for the Westside Irrigation Company. The route of the under-construction San Pablo and Tulare Railroad, depicted by a dashed line bisecting the map, will terminate at a junction (near the “O” in “County”) between the towns of Ellis and Bantas on the original Western Pacific Railroad. That junction would become Tracy.

When the first Western Pacific was built here in the 1860s – before it was renamed the Southern Pacific Railroad by its parent, the Central Pacific – the town of Ellis was developed around the railroad’s coaling station and its depots for both freight and produce. Bantas also had its own depot, while the Central Pacific’s main facility was located at Lathrop.

The Central Pacific had intended to build its main facilities at Stockton to serve the growing population of San Joaquin County’s largest city. The people of Stockton welcomed the opportunity to have a railroad depot to move their products and themselves across the United States, but they denied the Central Pacific the land needed to build large maintenance facilities for its locomotives, not wanting the smoke and soot that came with the big engines.

Undeterred, the Central Pacific’s controlling director, Leland G. Stanford, simply found a fairly unused stretch of land south of Stockton and had his surveyors plot out the maintenance facility there. He named this place Lathrop, after his wife’s maiden name. The location was perfectly situated on the line between Sacramento and the Bay Area, and became the connecting point for yet another extension of the CPRR, down the Central Valley to Southern California, paralleling for the most part the current-day route of Highway 99.

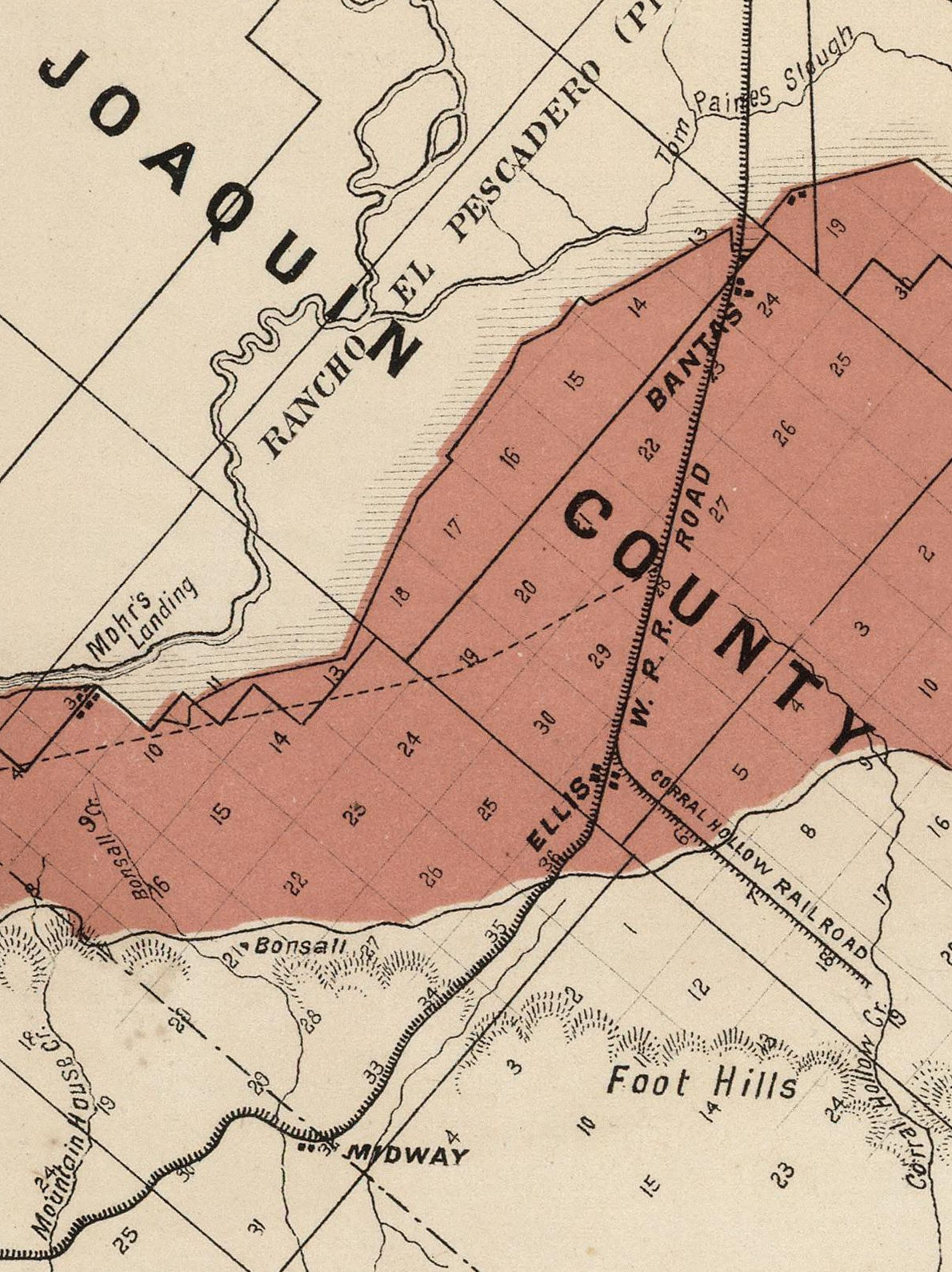

The Central Pacific’s May 1870 timetable shows stops at Midway, Ellis and Bantas on the way east from Oakland via the original Western Pacific … but no Lathrop or Tracy (yet).

The Central Pacific grew rapidly and soon made plans for another extension, this one creating a shortcut to its Northern Railway subsidiary at Martinez on the edge of San Pablo Bay down to the CPRR’s existing Western Pacific line from the Bay Area to Lathrop. Sensing the chance to grow their town, the residents and business owners of Bantas pushed to have the extension line terminate in their town.

They apparently didn’t push hard enough.

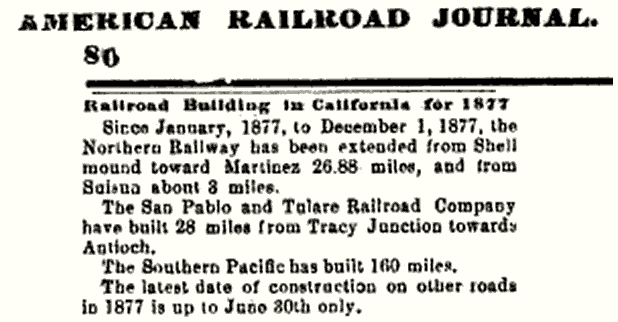

The 1877 edition of the American Railroad Journal reports that 28 miles of track have been built from Tracy Junction towards Antioch – about to Brentwood – on the new San Pablo & Tulare line.

Instead, a decision was made to end the new line – incorporated as the San Pablo & Tulare Extension Railroad Company – at a spot about halfway between Bantas and Ellis on the original Western Pacific transcontinental mainline, where it would meet up with yet another new CPRR subsidiary line that would run down the verdant west side of the San Joaquin Valley to Los Banos and, from there, on to Los Angeles and New Orleans as part of what would become the railroad’s “Sunset Line.”

By the end of 1877, nearly thirty miles of the new San Pablo & Tulare’s rails had been laid from the junction in Tulare Township to the outskirts of present-day Brentwood.

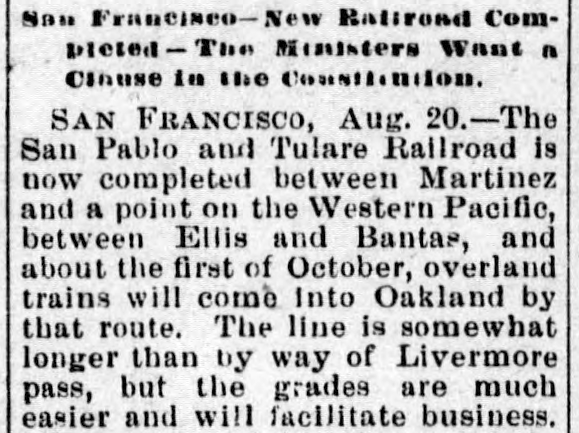

The Los Angeles Daily Herald of Wednesday, August 21, 1878, proclaims that the San Pablo & Tulare is complete, and trains will begin taking the line “about the first of October.”

By August 1878, the San Pablo & Tulare was complete from Martinez and, in the words of a contemporary newspaper report, “a point on the Western Pacific, between Ellis and Bantas.”

At this point, that “point” on the WP didn’t even have an official name yet – though it was irregularly (and perhaps informally) referenced “Tracy Junction” – but it was expected that trains would begin detouring on the SP&T route from Valley locations up and over to Oakland in early October of 1878, taking a “somewhat longer” route to the Bay Area than the previous transcontinental rail line over the Altamont and Livermore passes.

Being almost nearly flat, the grades (or slopes) on the new line were considered “much easier” than the climb over the steep Altamont Pass, which was projected as a means to “facilitate business” of both a freight and passenger nature.

(The railroad was required to couple on helper locomotives at Ellis in order to drag heavier trains over the Altamont; it was hoped that the new line would eliminate the cost of those helpers returning “light,” which produced zero revenue but required additional fuel and water, and wages for a full engine crew in both directions.)

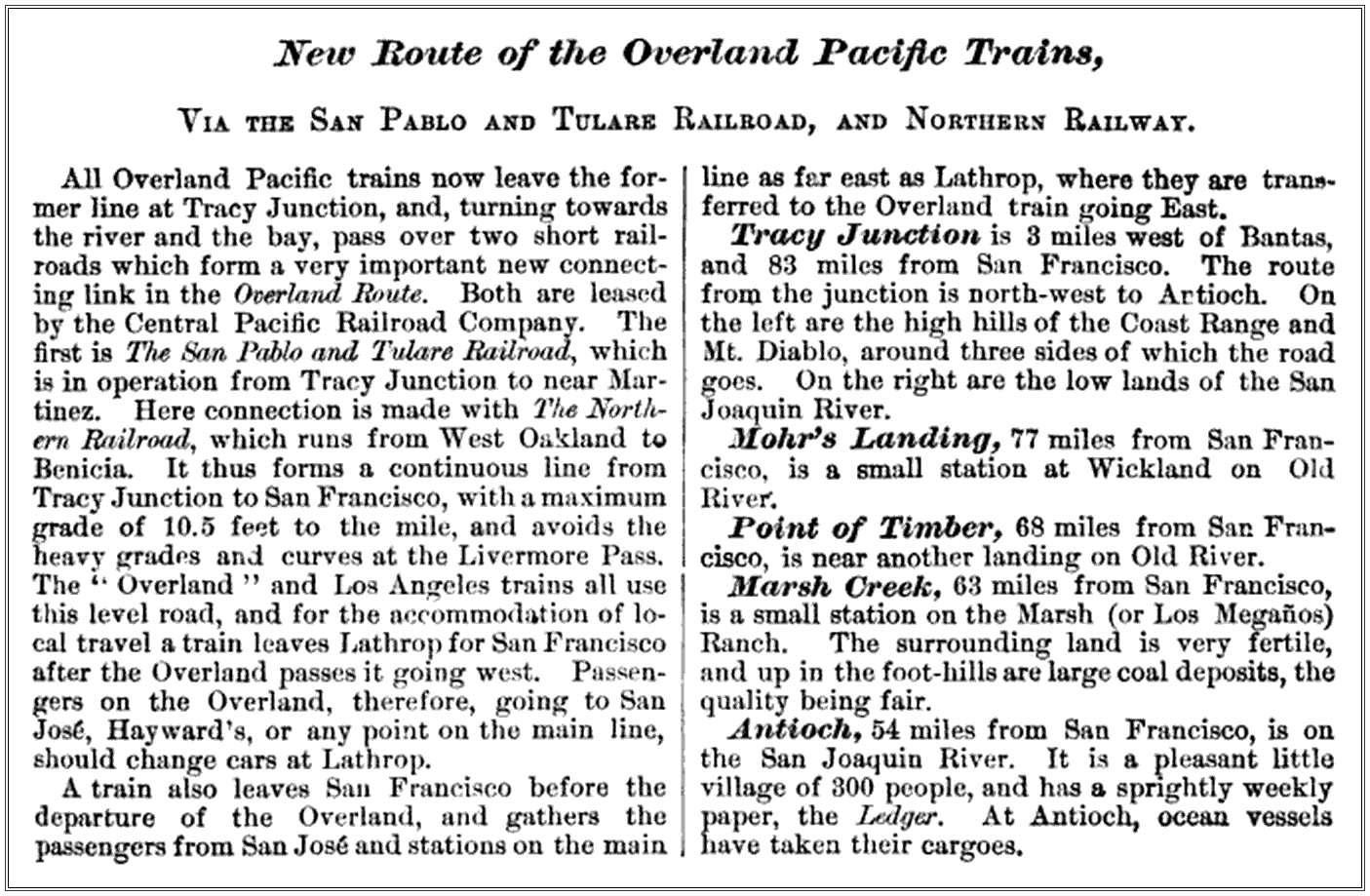

By the end of 1878, travel journals published descriptions of the new route along the San Pablo & Tulare extension that was now carrying overland trains headed for the Pacific Coast.

A description of the route from Tracy Junction via the new San Pablo and Tulare Railroad, from ‘The Pacific Tourist’ (1878)

But now the Central Pacific had facilities at Lathrop and Ellis, plus another depot at Bantas and another in the foothills at Midway – but nothing at the junction where its rails from east and west and north and south would soon meet. Passengers heading into the Bay Area were transferred to trains at Lathrop, but there was nothing “there” at the new junction but a shack and a switchman to throw the switch to send trains to their appointed destinations.

After careful deliberation, and with a logical view of what made the best sense from an operating perspective, the decision was made to relocate all of the railroad’s local operations to the new junction – now known more regularly as Tracy Junction. A town would soon grow up around that one shack and that one switchman.

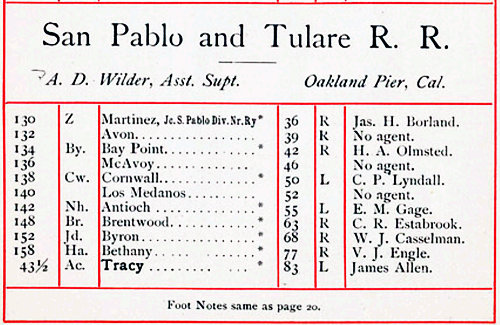

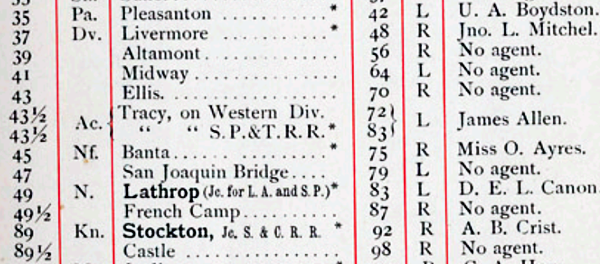

Depots along the San Pablo & Tulare Railroad, 1884

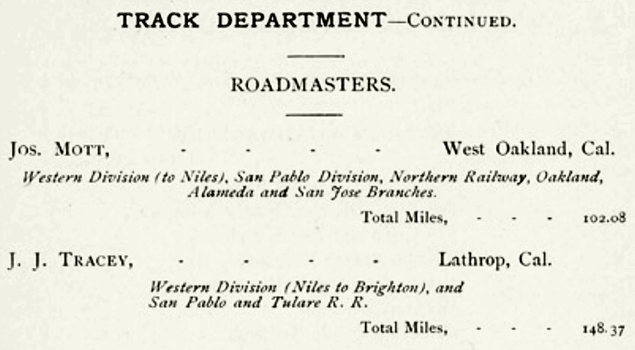

The Central Pacific’s roadmaster for the district was J.J. Tracey, headquartered at Lathrop and in charge of all of the railroad’s operations from Niles (Alameda County) to the west through to Brighton, just outside of Sacramento, the next main division point on the CPRR, covering nearly 150 miles of track – as well as the recently-completed San Pablo & Tulare Railroad from Antioch down to the newly-created Tracy Junction.

Lathrop roadmaster J.J. Tracey in the Central Pacific’s 1884 directory

As the extension from San Pablo was completed and construction on the new “West Side” line continued, Tracey oversaw the closing down of the CPRR’s operations at Ellis and the construction of engine facilities, depots and docks at the new junction.

Many residents and businesses in Ellis simply pulled up stakes – and pulled down their buildings – and also moved to the new junction, essentially abandoning the old town, which became the far western end of the railroad’s huge yard near what is now Corral Hollow Road near Schulte Road.

Ellis, Tracy and Banta in the 1884 Central Pacific Railroad Guide, showing Tracy as a junction on both the CPRR’s Western Division (ex-Western Pacific route) and its San Pablo & Tulare extension.

Under Tracey’s watch, the CPRR – which consolidated its various lines under the Southern Pacific name in 1888 – began to construct its vast, sprawling rail yards at the junction. In time, two large roundhouses were built here for repairing and servicing locomotives, along with facilities for refilling engines with fuel, water and sand, plus produce and freight docks, and a passenger station that was soon outgrown and replaced by a larger depot. (The passenger depot was located across Central Avenue from where the current Tracy Transit Center now stands.)

Denied the chance to become a major junction on the CPRR, Bantas over time lost its extraneous “s” and, in 1902, its railroad depot was torn down and rebuilt in Benicia, where it remains standing to this date.

Midway, up in the Altamont foothills, also lost its depot, but kept its United States Post Office open until 1918. The last Southern Pacific train rolled through Midway in the 1990s after which the SP’s rails were pulled up the rest of the way to Altamont; aside from a few scattered ranches, the area remains largely unpopulated.

Ellis, still holding its place on the map in 1942

The town that grew up around the junction became known as “Tracy Junction,” which was soon shortened to “Tracy,” ostensibly getting its name from a fellow named Lathrop Josiah Tracy who was – depending on the source1 – the Ohio-born director of the Sandusky, Mansfield and Newark Railroad in his home state and a very distant cousin of Leland Stanford’s wife and/or the “admired” former employer of one J.H. Stewart, who served as construction superintendent of the San Pablo & Tulare extension and had once worked for Mr. Tracy in Ohio.

In either case, it is not commonly believed that Lathrop J. Tracy ever visited the fine city that is purported to bear his name.

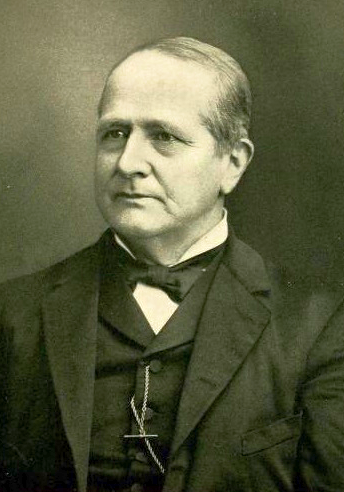

Lathrop Josiah Tracy

(1825-1897)

- See Sam Matthews’ Tracy Press column from May 2018 on this subject.