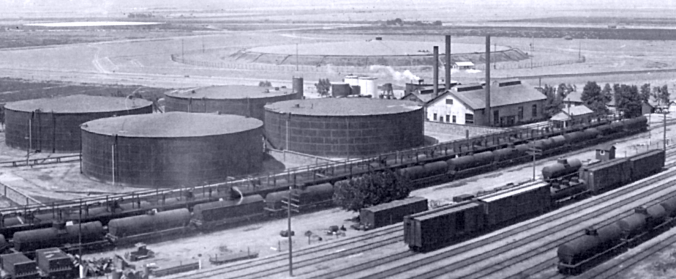

For decades, oil from Kern County was transported by rail in tank cars (appropriately dubbed “oil cans”) to this Associated Oil storage facility in Tracy, which served as a way station as the oil traveled to Port Costa.

In the aerial photo from 1926 (shown above and below), the tracks heading to the right are part of the Mococo Line, which is now a seldom-used single track that extends up past Mountain House through Byron and Brentwood (alongside the Byron Highway) into Antioch and Pittsburg.

In the distance, just right of center in the photograph is an oil reservoir (also known back then as the “Gravel Pit”), which was located approximately where Alden Park is today.

The Mococo Line was fundamental to the creation of the city of Tracy, which was founded in 1878 when the nearly fifty-mile-long line was opened between Martinez and here.

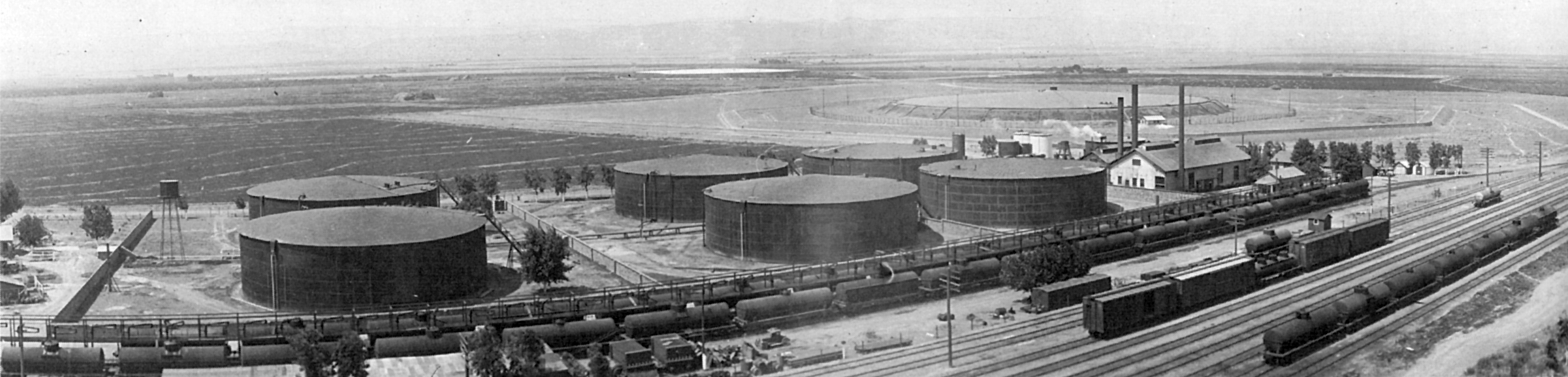

The oil terminal in Tracy from the air in 1957. Note that Tracy Blvd. (then McKinley Avenue) did not cross the tracks at the time, and neither did Oil Road (now also Tracy Blvd.) which at time looped around the six oil storage tanks.

Originally constructed as the San Pablo & Tulare Railroad, it was built as an extension – a shortcut, as it were – connecting the Central Pacific’s established northern line near San Pablo Bay and its line through the San Joaquin Valley via Stockton and Lathrop over the Altamont and on to Oakland and San Jose.

The extension was known as the San Pablo & Tulare because Tracy didn’t exist at that time; the district, which included the villages of Ellis and Banta, was known collectively as Tulare Township, hence the “Tulare” in the railroad’s name. (The SP&T was consolidated into the Southern Pacific Railroad, the successor to the Central Pacific, in 1888, ten years after Tracy was founded.)

All that currently remains of this facility today is a group of hillocks at the corner of Tracy Blvd. and Beechnut Avenue, across from the city’s corporation yard.

Contaminated soil in the area led to a landmark court case, Cose v. Getty Oil Co., over who was responsible for waste from the tanks that had seeped into the soil surrounding the “Gravel Pit.”

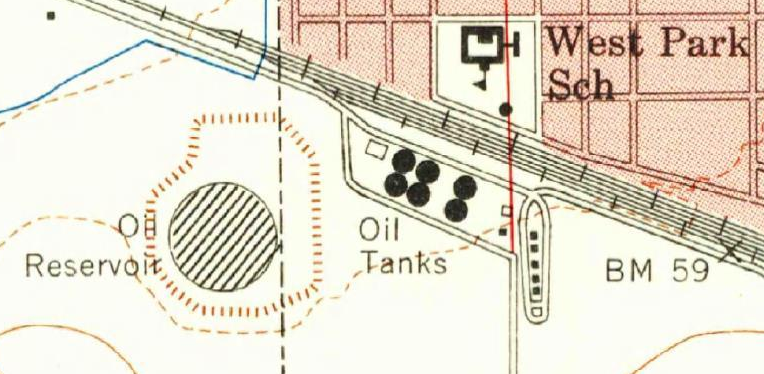

ABOVE: An excerpt from a 1955 USGS map of Tracy, showing the Tank Farm area. Note that the current Tracy Boulevard, previously known as Oil Road, did not extend across the tracks here at this time.

ABOVE: A Google Earth aerial view of the Tank Farm area as it appeared in 2013. Tracy Blvd. curves from top to bottom at right, with Alden Park in the lower-left corner.

Southern Pacific Train 51, the westbound San Joaquin Daylight, roars past the Tank Farm (at right) on July 7, 1956, on its way to Martinez and Oakland by way of the Mococo Line, in this photo by E.K. Muller

(Western Railway Museum Archive)

ABOVE: A typical Associated Oil tank car. The San Francisco-based company used “Tidewater” and “Flying A” as brand names.

Special thanks to the Western Railway Museum for permission to include E.K. Muller’s majestic 1956 photograph of the San Joaquin Daylight in Tracy (Negative No. 90126) in this article.